RCL Epiphany 4C

30 January 2022

Holy Trinity Anglican Cathedral

New Westminster BC

One of the downsides of being an academically trained liturgist is that I am frequently irritated by what I see on television or in films. For example, in the film Master and Commander, set in the Napoleonic Wars, there is a scene of the captain conducting a burial at sea using The Book of Common Prayer. The crew begin to recite the Lord’s Prayer and say, ‘Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.’ But, as I know, in the prayer book that they would be using, the phrase goes, ‘Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive them that trespass against us.’

You never want to be seated next to me if the television program or film we’re watching has a wedding scene. It never fails, especially when the scene is set it what appears to be an Anglican church, that the couple beams at each other during the exchange of the vows and says, ‘I do.’ Anglican wedding services have always asked each of the partners individually, ‘Will you give yourself . . . to love . . . , to comfort . . . , to honour and protect . . . ; and forsaking all others, to be faithful . . . so long as you both shall live?’ To this question the individual responds, ‘I will.’

When the Christian community gathers to give thanks for the marriage that is taking shape and to bless the commitments and vows being made, we are not interested in whether the couple does love each other. They probably do, especially in this moment. What we’re interested in is whether they will love each other. Will they continue build and strengthen their relationship and endure and persevere ‘for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health, to love and to cherish for the rest of (their) lives.’ Love, in the Christian tradition, is a choice we make each and every day, a decision to fulfill our baptismal promises in this particular and intense relationship.

· Love means saying we’re sorry and repenting.

· Love means seeking and serving Christ in the one to whom we’ve committed our life, loving them as our closest neighbour.

· Love means striving for justice and peace in our own household by respecting the dignity of those to whom we are most closely bound.

Love means this and so many other things. Love is more than a feeling; love is a choice, a verb of action, more than some cozy sensation akin to sitting in front of a fire on a cold winter’s day with a warm beverage, more than a romantic sentiment on a greeting card. Love is hard work.

That love is hard work is, I believe, at the heart of Paul’s famous ‘hymn to love’. We hear it read at weddings, portions printed in greeting cards and in other media. For so many people it’s become a kind of ode to romantic love, something humans often do when we want to tame something we realize may actually demand a great deal of us. And Paul does not mince words in describing how hard the work of love can be.

Think of all the things that Paul says are not love: impatience, unkindness, envious, boastful, arrogant, rude. When I look at that list and then look closely at my own life, I already feel a bit overwhelmed. I can hear the people in Corinth, after they heard these words, either hanging their heads in shame or sputtering defensively about all the times that they think Paul has been impatient or unkind or envious or boastful or arrogant or rude. After all, that’s what we’re tempted to do when someone holds up a mirror and shows us how we are seen by others.

But there is good news here as well. Paul reminds us that we are all works in progress. This is not an excuse to continue to shirk our responsibility to love others and ourselves as God has loved us in Christ, but a reminder of our human limitations even as we await the fulfillment of God’s promises in the age to come. I find Paul’s reminder helps me as a tool of self-reflection by taking the risk of delving into why I’m impatient or unkind or envious or boastful or arrogant or rude. For example, I tend to envious of what I perceive as the advantages of others when I am seemingly blind to the advantages and gifts that have come to me, unexpectedly and undeservedly. I tend to be impatient when other people seem to refuse stubbornly to look at the world as I see it – how rude!

Certainly two years of a pandemic has stressed our ability to love as Christ loved us and as Paul exhorts us to love. For some of us our resources of good will have been seriously drawn down. For others of us we protest perceived wrongs and injustices rather than acknowledge that we do not live in a perfect world, and we are not led by perfect leaders. Perhaps more ominously, we seek scapegoats to blame for all our perceived wrongs and purposely hide all our mirrors so that we can avoid real self-examination. Just like the people of Nazareth are outraged when Jesus tells them that his ministry leads him beyond the confines of his hometown and province and into the wider world of non-Jews, women and others who are not socially acceptable folk.

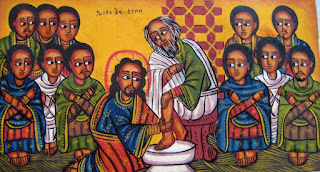

Love, the kind of love God shows to us in the creation of the universe, in the life, death and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth, in the renewing and life-giving power of the Holy Spirit, never ends because God’s work is not yet finished. You and I, as imperfect as we are, are agents of that work in this time and place. From time to time we even catch a glimpse of ourselves as God is leading us to become: icons that are not perfect but faithful representations of the world as it can be, not just in some unknown future, but here and now. Love is hard work, but it is the only work worth doing.