Liturgy Pacific is the on-line presence of Richard Geoffrey Leggett, Professor Emeritus of Liturgical Studies at Vancouver School of Theology. Here you will find sermons, comments on current Anglican and Lutheran affairs and reflections on the need for progressive orthodox Christians to re-claim our place on the theological stage.

Monday, April 17, 2023

Saturday, April 15, 2023

Mission, Power and Choice: Reflections on John 20.19-31

Mission, Power and Choice

Reflections on John 20.19-31

RCL Easter 2A

16 April 2023

Holy Trinity Anglican Church

New Westminster BC

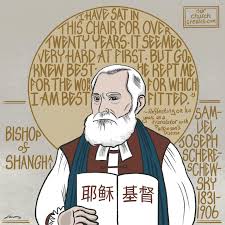

In 1859 a recently-ordained deacon embarked from California on board a ship bound for Shanghai. His name was Samuel Isaac Joseph Schereschewsky and he would spend the next forty-seven years of his life as a Christian missionary, bishop, educator and translator in China.

Schereschewsky had already had an incredible journey, geographically and spiritually, before boarding that ship at the age of twenty-eight in 1859. Born in Lithuania in 1831 to parents who were orthodox Jews, Schereschewsky was intended for the rabbinate. But an encounter with a New Testament in Hebrew during his rabbinical studies convinced him that Jesus was the long-promised Messiah. His spiritual journey then led him from his rabbinical college in Ukraine to Germany and then to the United States, from the messianic Jewish movement to the Baptists to the Presbyterians and finally to the Episcopalians.

He eventually became Bishop of Shanghai in 1877 and was instrumental in establishing educational institutions and in translating the Scriptures and liturgical materials into various Chinese dialects. But just four years into his episcopal ministry, Schereschewsky was stricken by a stroke. He resigned as bishop in 1884 and spent the remainder of his life as a translator. By the end of his life he was able to use only two fingers on one hand to type, but he persevered. When asked by a reporter about his struggles and frustrations as a result of the stroke, Schereschewsky said, ‘It was hard at first. But, in the end, God enabled to do the ministry I was suited to do.’

Schereschewsky has always been a favourite modern saint of mine. The bishop who ordained me, Bill Frey, always wanted to name a new parish after him but never did. In Schereschewsky I have found a living example of some ideas I see in today’s familiar gospel reading from John.

It is Easter evening and the Eleven along with other disciples are hiding, afraid of the religious authorities and the Romans, uncertain about the future and confused by the reports that their Lord is not dead. Then Jesus comes into their midst, through the locked doors of the room and of their hearts. In the space of a few moments he transforms them into a community with a purpose: “As the Father has sent me, so I send you.” (John 20.21c NRSVue) They are no longer a community of disciples, that is to say, students or protégés. They are now an apostolic community, ambassadors, agents, the continuing presence of Christ in the world.

It’s not enough, though, to be commissioned, to be called, they, and we, need to know what it is that God would have them, us, do: “(Jesus breathed on them and said to them, ‘Receive the Holy Spirit. If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven them; if you retain the sins of any, they are retained.’” (John 20.22a-23)

They, and we, are given power to liberate or to oppress. Throughout the Gospels it is undeniably clear that God in Jesus is at work liberating the creation from all that oppresses us, all that binds us. God frees us form our fear of death; God frees us from our inability to become more fully human in the image of God and the likeness of Christ; God frees us from our selfishness and misuse of the resources God has entrusted to us.

But in giving us the power to heal, God has also given us the power to hurt. It is the divine dilemma: by entrusting to us the power to do what we know God wants us to do, God must take the risk that we will choose to walk in other paths and to ignore the ‘better angels of our nature’.

In Thomas the Eleven and the others face the first test of their commitment to the ministry of Jesus and the power that Christ through the Spirit has breathed upon them. Do they embrace Thomas despite his doubts and sarcastic remarks or do they shun him? They choose to embrace him and, in this sign, this work of God, we are able to “continue to believe that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God, and that through believing (we) may have life in his name.” (John 20.31bc)

More than one hundred and twenty-five years ago Samuel Schereschewsky came to believe that Jesus was the promised Messiah and used the power given to him to build bridges between China and North America. His legacy continues in St. John’s College at UBC, founded in 1997 by alumni of the original college in Shanghai, closed by the Communist government in 1951. By the Spirit’s power Schereschewsky moved the two fingers left to him to continue the work of translating the Scriptures, a translation which is still used by Chinese Christians to this day. He accepted the commission and used the Spirit’s power to build up and to heal, even when weakened and limited in his abilities.

Through our baptism, you and I have been incorporated in this ministry of liberation God began in Jesus and continues in and through us. We have been given power to heal or to hurt, to build up or to tear down. The choice always lies before us, just as it did when the Eleven and the others pondered how to solve a problem like Thomas.

Who are our Thomases? From what do they, do we, need liberation? On this Sunday, on every Sunday, on every day, Jesus has come through our locked doors and stands in our midst, waiting to see what we will choose.

Tuesday, April 11, 2023

Saturday, April 8, 2023

Walking Through Closed Doors: Reflections on John 20.1-18

RCL Easter A

9 April 2023

Holy Trinity Anglican Cathedral

New Westminster BC

In the early spring of 1960 a small Lutheran congregation in Martha’s Vineyard offered a $100 prize in a local poetry competition. The prise was won by a student from Harvard who wrote a poem entitled ‘Seven Stanzas for Easter’. He donated the prize money, with a little over $1000 in today’s dollars, to the congregation. His name was John Updike.

John Updike went on to become one of the significant American writers of the later decades of the twentieth century. In the view of some critics he ranks among the greatest American writers, while in the mind of other critics he was a voice of a conservative, uptight middle America. To this day he remains a widely read author as well as a much debated one. But his poem reveals a deep faith in the reality, the physicality of the resurrection, a faith he seems to have kept throughout his life.

Make no mistake: if He rose at all

it was as His body;

if the cells’ dissolution did not reverse, the molecules

reknit, the amino acids rekindle,

the Church will fall.

It was not as the flowers,

each soft Spring recurrent;

it was not as His Spirit in the mouths and fuddled

eyes of the eleven apostles;

it was as His flesh: ours.

The same hinged thumbs and toes,

the same valved heart

that-pierced-died, withered, paused, and then

regathered out of enduring Might

new strength to enclose.

Let us not mock God with metaphor,

analogy, sidestepping, transcendence;

Making of the event a parable, a sign painted in the

faded credulity of earlier times:

let us walk through the door.

The stone is rolled back, not papier-mâché,

not a stone in a story,

but the vast rock of materiality that in the slow

grinding of time will eclipse for each of us

the wide light of day.

And if we will have an angel at the tomb,

make it a real angel,

weighty with Max Planck’s quanta, vivid with hair,

opaque in the dawn light, robed in real linen

spun on a definite loom.

Let us not seek to make it less monstrous,

for our own convenience, our own sense of beauty,

lest, awakened in one unthinkable hour, we are

embarrassed by the miracle

and crushed by remonstrance. [1]

Ever since that first Easter some two thousand years ago Christians and our critics have struggled to explain what happened to transform a small group of frightened and for most part working-class, uneducated Palestinian Jews into a movement that would eventually include two billion people in more than 45,000 distinctive expressions of the good news of God in Christ. To some the resurrection is a spiritual experience, a mystical experience, an affirmation of our deepest hope that there is more to life than what we experience with our five senses.

To others the resurrection is a metaphor, a story told to re-assure us that evil is always overcome by good, that life is stronger than death, love stronger than hate, justice stronger than oppression. To some the resurrection is a story from a more naïve past when people lived in a world populated by gods, demi-gods and other mysterious beings.

All these ways of understanding the resurrection offer us a means of comprehending what is, honestly compels me to say, is incomprehensible, whether two thousand years ago or today. But these different ways, as well as all the other ways, do not describe what I believe to have happened on this morning outside Jerusalem.

I believe that God raised Jesus of Nazareth from the dead in the fullness of his humanity, in the fullness of the person that Mary Magdalene, Peter, John and all the other witnesses to the resurrection knew and loved and mourned and touched. There was, to be sure, something different about him, a quality of life that was, if you wish, other-worldly. But it was Jesus, the Jesus who taught and healed and suffered and died.

When we confess our faith in the resurrection, we are confessing our belief that matter matters, that God cares for the totality of what it means to be a human person – our bodies, our minds, our hearts, our souls, our memories, all that makes me me and you you. To believe in the resurrection of Jesus is to believe that what we see and touch and celebrate in creation is the result of God’s loving intention. The physical is not an accident but the result of God’s choice to make room for us in the kosmos.

Gretchen Ziegenhals writes that “ . . . if we believe in the resurrection of the body, we will respect all bodies here among us – Black, brown and white bodies; rich and poor; male, female, trans and nonbinary; straight and gay; friend and stranger; young and old.” [2]

While we wait for the resurrection – for our bodies and those of our loved ones to be ‘regathered’, as Updike describes – there is embodied work for us to do now, despite our pandemic limitations: the work of justice and equity; the work of feeding and housing; the work of sharing bread, employment and fellowship; the work of making room for other voices and bodies; the work of ministering to the sick and the lonely in whatever ways we can. [3]

When I was younger and regularly singing in my parish choir, I realized that there were hymns that I did not enjoy singing. The tunes were lovely, but the words did not express what it meant to be a disciple of Jesus who was raised by God from the dead. Many of these hymns were the hymns of people who were oppressed and who struggled in their day-to-day lives. They were filled with hope ‘in the sweet by and by, when we’ll meet at that beautiful shore’. But I didn’t hear hope; I heard resignation and acceptance of the world as it is rather than working tirelessly and fearlessly for the world as God desires it to become.

I have no certain knowledge of when creation will become what God desires it to become. In the meantime I trust that God holds all the faithful departed in anticipation of that day when God’s purposes are achieved. In the meantime I pray that “we, who share [Christ’s] body, [may live] his risen life; we, who drink his cup, bring life to others; we, whom the Spirit lights, give light to the world . . . so that we and all [God’s] children shall be free”. [4] Why? Because God raised Jesus from the dead, everything that made Jesus Jesus, and, in so doing, has shown us that matter matters to God and that we, everything that makes us us, matters to God, now and in the age to come.

[1] John Updike, ‘Seven Stanzas for Easter’ (1960).

[2] Gretchen E. Ziegenhals, ‘Walking through closed doors this Easter – the resurrection of the body’ https://faithandleadership.com/gretchen-e-ziegenhals-walking-through-closed-doors-easter-the-resurrection-the-body.

[3] Gretchen E. Ziegenhals, ‘Walking through closed doors this Easter – the resurrection of the body’ https://faithandleadership.com/gretchen-e-ziegenhals-walking-through-closed-doors-easter-the-resurrection-the-body.

[4] The Book of Alternative Services (1985), 214-215.